Last month, I was finishing some edits on a piece about decolonising education. I explain how “historically, the British education system has neglected to meaningfully address that the entire project of British imperialism was specifically designed to destabilise indigenous cultures by limiting avenues of resistance and by extracting all its conceivable resources.” Colonialism sits at the core of many complex realities that various regions of the world are currently facing.

Note: It is worth mentioning the legacy of British rule in Palestine – the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the British Mandate for Palestine (1918–1948) have some bearing on the latest flare up of violence in the tragic Israel-Palestine conflict.

I was really fortunate that my particular English degree offered lots of progressive units that meant I got to study feminist, Marxist, post-modernist, post-colonial and psychoanalytic writers and thinkers. I was also allowed to come to Accra to do some self-initiated research for my undergrad dissertation in 2011. Although academia wasn’t for me – I found essay writing conventions unnecessarily restrictive – my exposure to that particular theoretical canon has served me well.

Recently, I’ve found myself drawn to the work of contemporary philosopher Miranda Fricker after coming across her theory of ‘testimonial credibility deficit’, where some experiences or opinions aren’t as likely to be regarded as rational, competent or credible as others because they belong to a minoritised group. Hard relate, y’know.

Her ground-breaking book, Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing (2007) sets out two main conceptual frameworks; ‘epistemic injustice’ and ‘hermeneutical injustice’.

Note: ‘Epistemic’ is the adjectival derivation of ‘epistemology’, the theory of knowledge. And ‘hermeneutical’ is the adjectival derivation of ‘hermeneutics’, the theory and methodology of interpretation.

These are both theories which can be boiled down to whether or not people have the tools to communicate within and across social spaces to describe experiences. Because the ways in which we each navigate our social worlds is basically interpretive – we place meaning on what we experience based on the knowledge we’ve already gained, through both observing and being active in social culture – it follows that the tools we each have to make sense of things are unevenly informed because of our differing lived experiences.

Sometimes, or often, actually, people don’t have the appropriate knowledge concepts within their internal library of language-based vocabulary or lived experience, to articulate the thought or situation that they’re trying to convey. Examples of this are super wide-ranging.

For example, in land disputes, indigenous peoples may not be able to gain back their ancestral homelands, because the ways in which they have traditionally staked this claim have often been invalidated by new social codes turned into laws by settler colonialists. Or that people who experience sexual harassment prior to the time when we had this critical concept (i.e., before Human Rights became normalised), for instance, might not be able to comprehend their own lived experience, let alone communicate it intelligibly to others.

Or that the origins of conventional beliefs about sexuality and gender binaries originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – times of extensive colonial expansion – and were brought to many regions around the world, which, prior to colonialism had broader conceptions of these things. Forced assimilation eroded typical ways of life, which, having no corresponding notions in neither the settler colonialists’ language nor culture, then became invalid.

So, we can see how, in the absence of conceptual and structural resources for addressing certain problems, it is useful to have a theory like Miranda Fricker’s. And in Fricker’s own words: “Hermeneutical injustice is: the injustice of having some significant area of one’s social experience obscured from collective understanding owing to a structural identity prejudice in the collective hermeneutical resource.”, Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing (2007), p. 155.

I’m feeling out what it would mean for intimate relationships if we are to analyse them for hermeneutical marginalisation.

Let’s say your date for the evening is a cis man who’s been brought up within a culture of Machismo (maybe he’s from Latin America). He might not be able to comprehend egalitarian views on mutual sexual pleasure, and so when you go back to his place (which is in a gentrified area of a cosmopolitan city), he pumps away without any regard to your own experience. He might not be able to approximate the concept of a mutually pleasurable sexual encounter, because it’s not something that has ever cropped up in his experience of social discourse.

Or, you’re someone who has yet to make their sexual debut and actually hasn’t had any sex education at all. You’re excited for your wedding day (and night) when you’ll be marrying your steady boyfriend from church. Your Bible study group leader has spoken to you and your husband-to-be about what to expect on your wedding night, and you really want to try to satisfy him. But when you both head to your hotel room after a wonderful day of celebrations, you and he are both at a loss for what to say or do to initiate sexual intimacy. Neither you nor he have the language to express a physical desire which is borne out of genuine love, respect and excitement. You spend the night listening to him faking sleep, while you also fake being asleep.

I’m hoping that I’ll be able to consider all kinds of other dynamics too, like how social norms leverage shame as a tool to disallow certain behaviours as a tool of control. And also how we experience the feelings of threat and fear in our bodies – these emotions can cause immobility, which stops us from being able to communicate with intention.

Once these types of marginalisation become apparent within interpersonal relationships, the question then becomes; how can we meaningfully communicate across these kinds of conceptual divides? We all have some sense of awareness that social discourse can be either more or less difficult depending on the circumstances (for example, whether you speak the same language or dialect). But we aren’t very used to weighing up how much of our shared social experience (for example, whether we have a similar vocabulary range) is doing the work of understanding the situation.

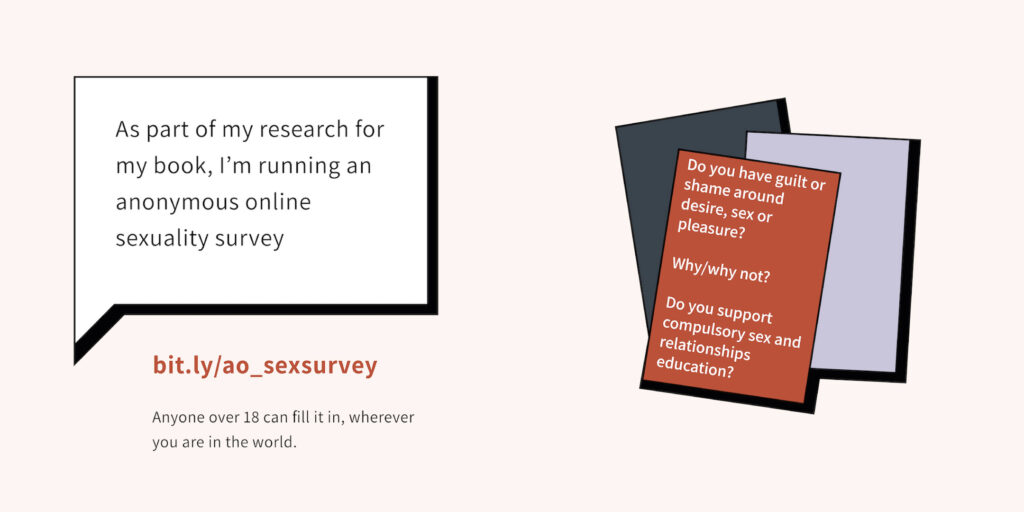

I’m also thinking about how intentionally ‘holding space’ alongside watching for all the social cues we transmit non-verbally, can help foster a more socially aware kind of listening. More on this next in next month’s mailout. In the meantime, please do fill in/share my anonymous sexuality survey. All of the responses (53, so far) are helping me make connections between the ways in which we’ve been socialised and our relationship to sexuality.

Survey link: bit.ly/ao_sexsurvey

[Image description: White speech box with black border shadows. Black text ‘As part of my research for my book, I’m running an anonymous online sexuality survey’. Dark orange text ‘bit.ly/ao_sexsurvey’. Black text ‘Anyone over 18 can fill it in, wherever you are in the world.’ Picture of coloured rectangles placed at angles with black border shadows. White text ‘Do you have guilt or shame around desire, sex or pleasure? Why/why not? Do you support compulsory sex and relationships education?’ on top rectangle]

NB. For anyone who’s interested, I’ve taken the survey myself and made the answers available here.

Glossary

‘Balfour Declaration’ – a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, then an Ottoman region with a small minority Jewish population

British Mandate for Palestine (1918–1948 – the outcome of several factors: the British occupation of territories previously ruled by the Ottoman Empire, the peace treaties that brought the First World War to an end, and the principle of self-determination that emerged after the war

‘epistemic injustice’ – distributive unfairness in respect of epistemic goods such as information or education

Feminism – a range of social movements, political movements, and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes

‘hermeneutical injustice’ – the injustice of having some significant area of one’s social experience obscured from collective understanding owing to a structural identity prejudice in the collective hermeneutical resource

hermeneutical marginalisation – the treatment of a person, group, or concept as insignificant or peripheral owing to a structural identity prejudice in the collective hermeneutical resource

machismo – exaggerated pride in masculinity, perceived as power, often coupled with a minimal sense of responsibility and disregard of consequences

Marxism – the political and economic theories of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that are used understand class relations and social conflict

Post-colonialism – the historical period or situation representing the aftermath of Western colonialism; the term can also be used to describe the concurrent project to reclaim and rethink the history and agency of people subordinated under various forms of imperialism

Post-modernism – the late 20th-century philosophical movement characterised by a general suspicion of reason and sensitivity to the role of ideology in asserting and maintaining political and economic power

Psychoanalytic criticism – adopts the methods of ‘reading’ employed by Freud and later theorists to interpret texts. It argues that literary texts, like dreams, express the unconscious desires and anxieties of the author

settler colonialists – a form of colonialism that seeks to replace the original population of the colonised territory with a new society of settlers – typically organised or supported by an imperial authority

If you would like to support the writing I share here, please consider becoming a paid subscriber of ‘She Dares to Say’.